History of Forensic Science

Welcome to the history of forensic science page. The aim of this section of the website is to highlight notable forensic landmarks and developments.

Want To Study Forensics/CSI?

The concept of applying 'scientific' principles to legal questions has a long and intriguing history. For example:

- In 44BC following the assassination of Julius Caesar the attending physician proclaimed that of the 23 wounds found on the body ‘only one’ was fatal.

- In the 5th century Germanic and Slavic societies were believed to be the first to put down in statute that medical experts should be employed to determine cause of death.

- In 1247 the first textbook on forensic medicine was published in China which among others things documented the procedures to be followed when investigating a suspicious death.

- In medieval England pressure from the church halted the practice of hanging women thought to be pregnant. A convicted woman could escape the death penalty if she ‘pleaded her belly’ providing a physician could prove that she was in fact pregnant.

- Inspired by the study of anatomy medicolegal textbooks begin to appear by the end of the 16th century.

- The 1887 coroners act ensured that an integral part of the coroners’ role was to determine the circumstances and the medical causes of sudden, violent and unnatural deaths.

The Rise of Forensic Medicine

(Information courtesy of The National Library of Medicine)

Forensic medicine, also called "medical jurisprudence" or "legal medicine," emerged in the 1600s. As European nation-states and their judicial systems developed, physicians and surgeons participated more frequently in legal proceedings.

|

By the late 1700s, medical jurisprudence had become a standard subject in the medical curriculum. In the early 1800s, Parisian medical professor Mathieu Orfila and others began to intensively study poisons and the decomposition of bodies. |

|

Medico-Legal Questions

Forensic medicine first appeared as a distinct subject in works such as Paolo Zacchia's Questiones Medico-Legales (1621). These early treatises discussed medical questions commonly treated in courts: How could one determine whether an infant was stillborn or the victim of infanticide? Whether a woman was a virgin? Whether a body found in water was someone who had drowned or the victim of a disguised homicide?

Proliferating Specialties

In the early 1800s, forensic medicine was not divided into distinct disciplines. Physicians and surgeons who performed autopsies and testified in court depended on a variety of sources for their income and provided expertise as needed. No regular system of payment was provided for expert testimony, laboratory analysis, or postmortem examination. Toxicology and forensic pathology were just emerging as distinct fields, and most autopsies were performed by physicians without any special training.

Post-Mortem Examination

In cases of homicide or suspicious death, in medieval England, the coroner, an appointed official who had no medical training, was required to make "a view of the body," a legal, visual inspection. Since then, medical professionals have played an increasingly important role in making views of the body. Physicians and surgeons have developed methods of seeing into the body through autopsy and post-mortem examination—making visible what the untrained, unequipped eye cannot see.

Post-mortem dissection, or autopsy, was among the earliest scientific methods to be used in the investigation of violent or suspicious death. Autopsy remains the core practice of forensic medicine. The postmortem examiner surveys the body's surface, opens it up with surgical instruments, removes parts for microscopic inspection and toxicological analysis, and makes a report that attempts to reconstruct the cause, manner, and mechanism of death. These clips from training films show some of the procedures of postmortem examination.

Tools of the Trade

The post-mortem examiner visually surveys the body's surface before opening and entering the body with the help of a scalpel and other instruments. After visual examination of the body cavities, the examiner removes parts for chemical analysis, inspection with a microscope, and other tests. Tools and tool kits specially adapted for use in autopsy first appeared in the early 19th century.

Changes After Death

Physicians and surgeons first gained practical knowledge of death and decomposition through handling and dissecting bodies obtained for anatomical study. Over the course of the 19th and 20th centuries, the study of the decomposed body and body parts—the effects of time, environment, and manner of death—became a vital part of forensic science.

Fauna of the Cadaver and Time of Death

In the 19th century, medico-legal researchers began studying patterns of insect colonization of the cadaver. Entomology, the study of insects, became one of the forensic sciences. By identifying the particular stages that insects go through as they develop on a dead body, and the succession of different species, forensic investigators attempt to determine where a victim died and estimate the time elapsed since death. These adult specimens represent some of the different insect species that colonize a cadaver.

Toxicology

As commercially manufactured poisons became increasingly available in the 19th century, poisoning became known as a "modern" and disturbingly hard-to-detect method of killing. In response, researchers developed toxicology as a specialized field of forensic medicine, and devised specific tests for poison, most famously the 1836 Marsh Test for arsenic.

The new science of toxicology was plagued by difficulties. In the courtroom and laboratory, seemingly reliable tests were shown to be flawed. But, over time, toxicology's trials led to better knowledge of the action of poisons and better methods of chemical analysis.

Microscopy

|

Mid-19th-century improvements enabled physicians to use microscopy in criminal investigations. The microscope made it possible to view tiny lesions, crystals, microorganisms, and the characteristics of hairs and fibers. By the mid-20th century, investigators were using microscopes to study tissues, wounds, and fluids from victims and suspects; to identify poisons in and around the victim's body; to examine minute amounts of trace elements; and to link the victim's body to the perpetrator and crime scene. |

Spectroscopy

Spectroscopy was born in the mid-17th century, when Isaac Newton discovered that a prism divides white light into constituent colors. Subsequent researchers discovered that specific substances, subjected to flame, give off unique patterns of light that show characteristic "emission" bands and "absorption" lines when cast through a prism.

By the 1870s and 1880s, spectroscopy seemed a promising new forensic technology. Further work on spectra analysis led to spectrophotometry and, more recently, mass spectrometry. In tandem with gas chromatography, mass spectrometry is now often used to identify and match organic and inorganic substances for forensic purposes.

Fingerprints

The first practical application of fingerprinting as a unique individual identifier came in the 1860s. Sir William Herschel, a colonial administrator in British India, used fingerprints to detect false pension claims. In an 1892 case in Argentina, Juan Vucetich became the first investigator to use fingerprints to help secure a conviction for murder.

A useable classification system was necessary before forensic fingerprinting could be put to practical use. In the 1890s and early 1900s, Vucetich in Argentina, and E. R. Henry in British colonial India and Great Britain, separately devised such systems. After a series of dramatic cases proved its merits, fingerprinting spread rapidly.

A Great Read

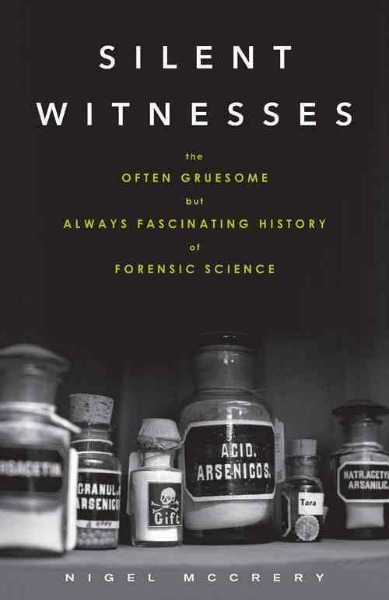

A crime scene. A murder. A mystery. The most important person on the scene? The forensic scientist. And yet the intricate details of criminal forensics work remain a mystery to most of us. In a book that is by turns fascinating and chilling, Nigel McCrery leads readers around the world and through two centuries to relate the history of forensics in accessible and entertaining prose. He introduces such colorful characters as Dr. Edmond Locard, the "French Sherlock Holmes"; and Edward Heinrich, the "Wizard of Berkeley," who is credited with having solved over 2,000 crimes.

All the major areas of forensics, including ballistics, fiber analysis, and genetic fingerprinting, are explained with reference to the landmark cases in which they proved their worth, allowing readers to solve the crimes along with the experts. Whether detailing the identification of a severed head preserved in gin, the first murder solved because of a fingerprint, or the first time DNA evidence was used to bring a sadistic killer to justice, Silent Witnesses provides dramatic practical demonstrations of scientific principles and demonstrates a truth known by all forensic scientists: people still have a story to tell long after they are dead.

See following link for full details.

Silent Witnesses: The Often Gruesome but Always Fascinating History of Forensic Science

Recent Articles

-

All About Forensic Science

Nov 12, 24 03:05 AM

A forensic science website designed to help anybody looking for detailed information and resources. -

The Role of Forensic Evidence in Criminal Defense Cases

Sep 05, 24 03:38 AM

Article exploring five key roles that forensic evidence plays in criminal defense cases -

The Evolving Role of Medical Science in Forensic Investigations

Aug 06, 24 03:35 AM

Insightful article exploring the critical role of medical science in forensic investigations.

New! Comments

Have your say about what you just read! Leave me a comment in the box below.